Prisoner Resistance

-

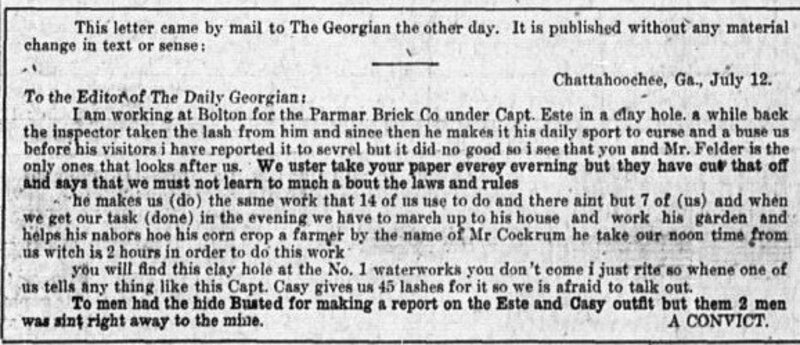

Letter written to the editor from an anonymous prisoner working for the Parmar [sic, Palmer] Brick Co. The anonymous prisoner describes the physical abuse of prisoners and the confiscation of newspapers among prisoners to bar them from news of the convict lease system's demise. Atlanta Georgian and News, July 27, 1908, p. 1.

Courtesy of Georgia Newspaper Project, Georgia Historic Newspapers.

-

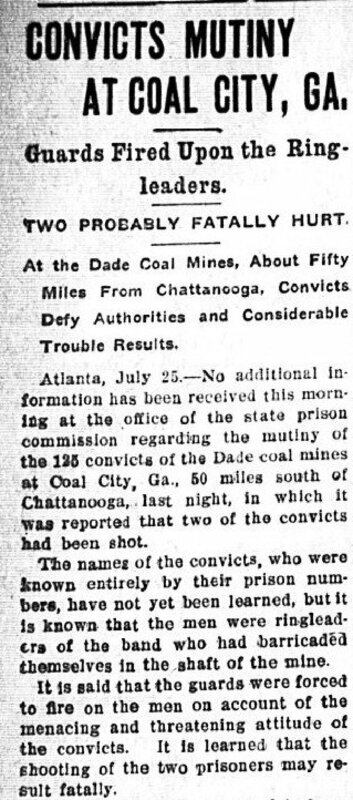

Newspaper report on a mutiny among prisoners at Joseph E. Brown's Dade Coal mines in Coal City. Several prisoners barricaded themselves in the mine, and the two prisoners who lead the protest were fatally shot. “Convicts Mutiny at Coal City, GA,” Americus Weekly Times-Recorder (Americus, GA), July 31, 1903, p. 2.

Courtesy of Georgia Newspaper Project, Georgia Historic Newspapers.

-

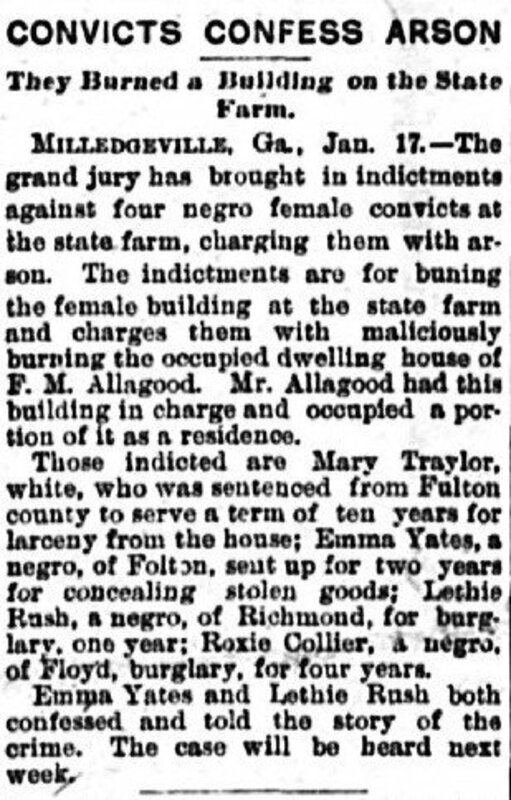

Report about white and Black female prisoners allying with one another to burn buildings at Milledgeville State Farm to protest working conditions. Athens Weekly Banner, Jan. 18, 1901, p. 1.

Courtesy of Georgia Newspaper Project, Georgia Historic Newspapers.

-

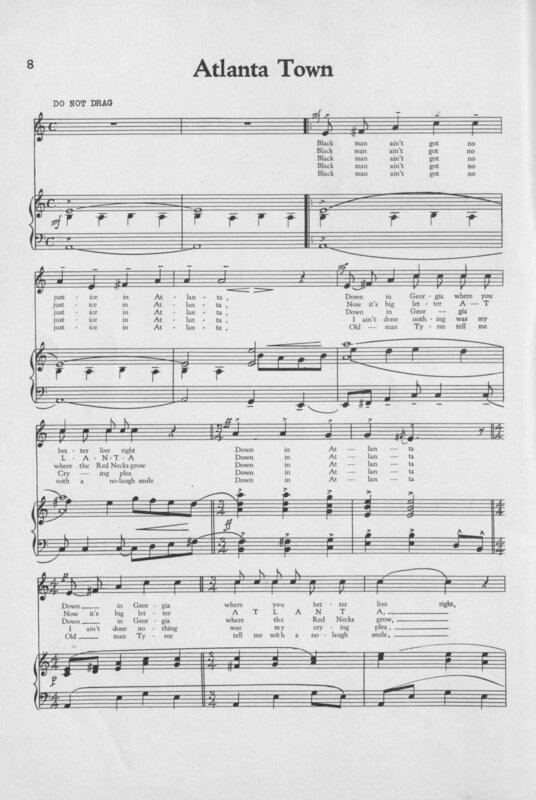

Work song called “Atlanta Town” which laments rampant racial injustice and the prison system in Georgia, particularly in Atlanta. From Me and My Captain: Chain Gang Negro Songs of Protest, 1939, p. 8.

Courtesy of Georgia State University. Libraries, M. H. Ross papers, Southern Labor Archives.

The ways in which imprisoned men and women responded to the experience of incarceration under the convict lease system often paralleled those of enslaved people. Prisoners used their bodies and their imaginations to resist the convict lease system. In several Georgia camps, male and female prisoners staged protests and mutinies. Letters from prisoners published in newspapers and in the autobiographies of former convicts recall slave narratives, reflecting on the physical, emotional, and social turmoil of incarceration.

Laments born of incarceration also took the form of work songs and field hollers reminiscent of slave spirituals. In musty, cramped mine shafts and under the sweltering Georgia sun, the dirges of prisoners floated on the air and were sent up to the skies. Like the “sorrow songs,” or the “rhythmic cr[ies] of the slave,” as W. E. B. Du Bois characterized slave spirituals and Black folk songs, prison work songs and field hollers were declarations of injustice, agony, and loss captured through words and rhythm. Songs were synchronized with prisoners’ work and sung in a call and response style. Tools became instruments: axes used for cutting timber and hammers used to pound railroad stakes supplied the beat and marked pauses between verses. Beatings, starvation, heat, homesickness, missing loved ones, and dreams of freedom were topics to which prisoners returned time and again in song. These melodies formed the soundtracks of prison farms, work camps, and chain gangs.