Associated Charities of Savannah & Helen Pendleton

-

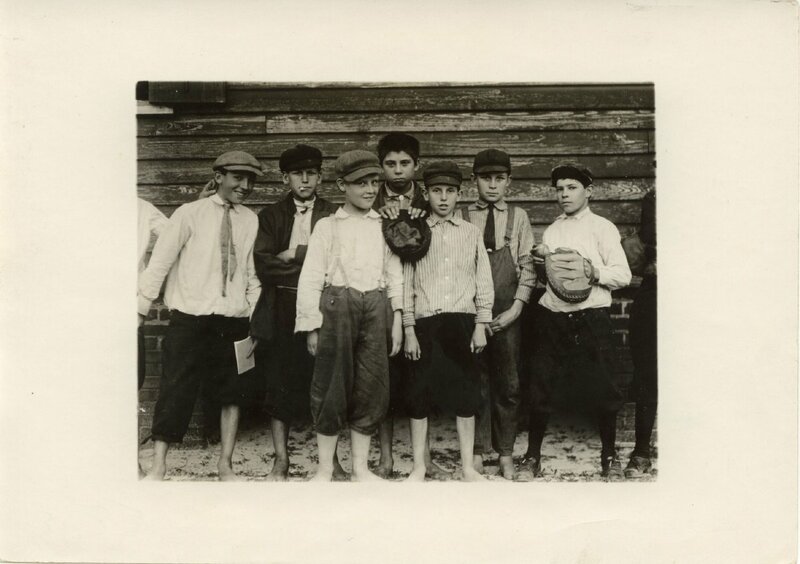

A group of young boys working for the Massey Hosiery Mills in Columbus, Georgia return to their jobs following their dinner break after working all day, 1913.

Courtesy of the Columbus Museum.

-

A young girl works a machine at the Walker County Hosiery Mills in LaFayette, Georgia, 1913. Photograph by Lewis Hine.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division via the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

-

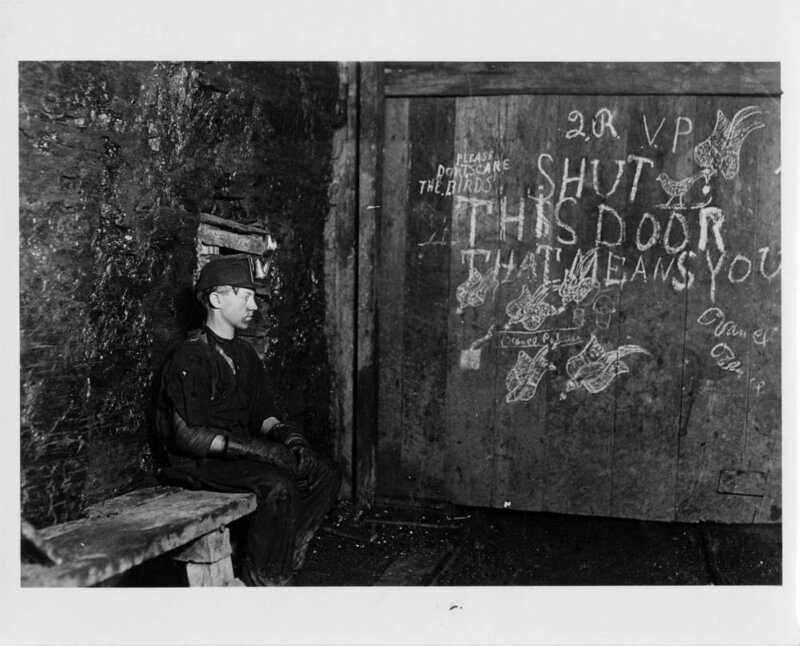

A fifteen-year-old boy works as a “trapper” in a coal mine earning seventy-five cents for ten hours a day in 1908. Trappers often worked long hours in total darkness and were responsible for opening and closing the wooden (trap) doors that allowed mining carts carrying coal to pass from one chamber to another.

Courtesy of Georgia State University. Special Collections, M. H. Ross Papers.

-

A young girl works as a spinner in a Georgia cotton mill in 1909. A spinner operated spinning machines by repairing breaks and snags in cotton fibers as they were drawn, twisted, and wound unto a spindle to make yarn or thread. Spinners usually worked barefoot because the floor beneath the spinning machines was soaked in oil from cotton fibers.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division via the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

In the New South Era, Georgia was eager to foster economic prosperity by attracting industrial opportunities to the state, arguing that “the factories need the children and the children need the factories.” By 1900, most of the 4,479 child laborers working in Georgia’s textile mills had begun their jobs under the age of twelve, toiling for long hours in dangerous factory conditions for ten to fifty cents a day. Georgian women launched an active campaign for child labor reform, often linking child labor issues with the need for improvements in education. In 1914, Helen Pendleton and the Associated Charities of Savannah played a significant role in passing the Sheppard Bill, a critical piece of child labor legislation that enforced standards in age and education. Speaking to the Georgia state legislature, Pendleton effectively countered the defenses offered by mill owners, who argued that restrictive laws would leave families destitute. Using research conducted by the Associated Charities of Savannah, Pendleton demonstrated that child labor contributed to a lack of schooling that kept children in poverty when they became undereducated, often illiterate adults who would never make more than $5 a week. Ultimately, the battle waged against adolescent workers in Georgia would prove long and difficult, but child labor laws coupled with improvements in education would help bring about better standards of living for children in the twentieth century.