Atlanta Anti-Tuberculosis Association

-

Page one of a 1919 report made by Lugenia Burns Hope outlining the recent work undertaken by the Negro Anti-Tuberculosis Association. The report discusses health campaigns initiated by Black female reformers and unsanitary conditions in Black neighborhoods caused by the neglect of city services.

Courtesy of Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library, Neighborhood Union Collection.

-

Page two of a 1919 report made by Lugenia Burns Hope outlining the recent work undertaken by the Negro Anti-Tuberculosis Association. The report discusses health campaigns initiated by Black female reformers and unsanitary conditions in Black neighborhoods caused by the neglect of city services.

Courtesy of Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library, Neighborhood Union Collection.

-

Patients stand in line for chest x-rays as part of a health program administered by the Atlanta Anti-Tuberculosis Association (ATA) in 1945.

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center, Atlanta Lung Association Photographs.

-

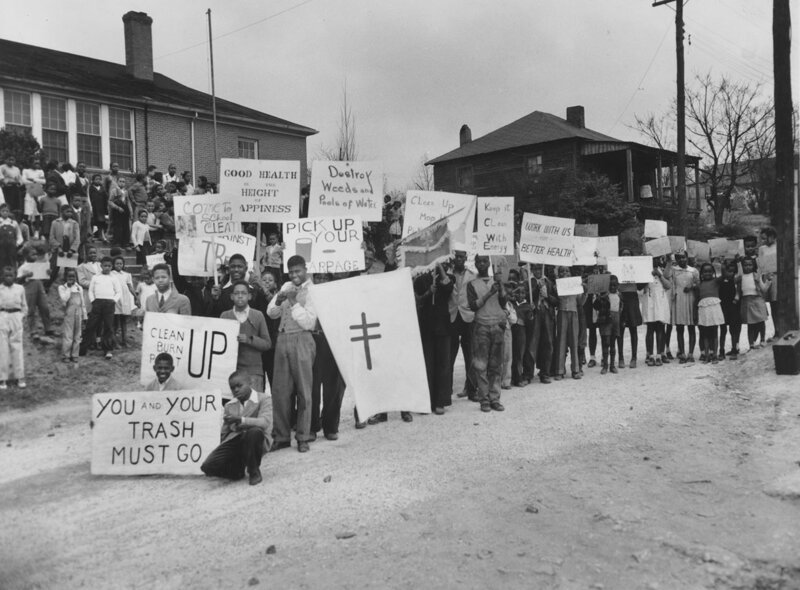

Children with posters advocating ways to prevent the spread of communicable disease as part of a clean-up campaign sponsored by the Atlanta Anti-Tuberculosis Association (ATA) in 1945.

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center, Atlanta Lung Association Photographs.

Tuberculosis was a significant public health concern for city dwellers at the turn of the twentieth century. In Atlanta, fear of contracting tuberculosis blended with prevailing racist attitudes and Black southerners were vilified as disease-ridden carriers who threatened to infect white communities. Believing Black Atlantans posed a health risk to the city, the Anti-Tuberculosis Association (ATA), composed entirely of white members, invited Black female reformers to develop a Black branch of the organization and the Negro Anti-Tuberculosis Association was formed. Women of the Negro ATA were able to take advantage of white anxieties concerning tuberculosis and challenge the neglect of Black citizens within the city’s public health agenda. Black women carved out a space as mediators between Black communities and white City Hall, where they confronted white supremacy by reallocating public resources to form a system of healthcare for Black Atlantans. This healthcare system was accomplished by spearheading countless reform campaigns, including establishing a network of free mobile medical clinics, organizing neighborhood cleanup campaigns, petitioning the city to take some responsibility for sanitary conditions in Black schools and neighborhoods, and forming public programs to spread educational information about tuberculosis. Black women who participated in Atlanta’s anti-tuberculosis movement were civic leaders who established a system of community-based programs that protected the health and welfare of Atlanta’s Black communities.