Telling LGBTQ+ Stories in Media

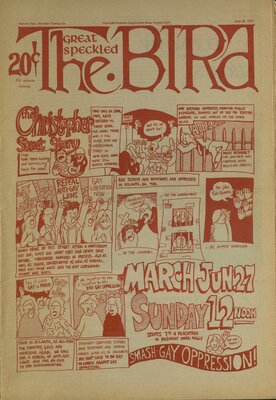

Before the 1970s, LGBTQ+ issues were rarely represented in mainstream Georgia newspapers, a fact that was made clear when the Atlanta Journal Constitution fired openly gay copy worker Charlie St. John in 1973 for placing Gay Pride fliers in employee mailboxes. The Georgia Gay Liberation Front had been irregularly publishing its own newsletter since 1971 (as the Good Gay Times or the Gay Times), and in 1974 Ray Green founded The Atlanta Barb, the first LGBTQ+ newspaper in the state, acquired the following year by GGLF activist Bill Smith. The Barb would run until 1977 and published on issues like police harassment, Pride, and the work of the Metropolitan Community Church. As advocacy groups began to develop within and outside of larger institutions, they printed their own newsletters: Atlanta’s First Tuesday Democratic Association, led by Gil Robison, published The Healthy Closet between 1978 and 1981 with the tagline “the only healthy closet is the voting booth.” The Atlanta Gay Center, which Robison founded in 1976, later published its own bi-weekly newsletter, The Atlanta Gay Center News (also known as Atlanta Gay Central or The News) in the mid-1980s, as did other political and advocacy organizations like AID Atlanta (AID Atlanta Newsletter, 1983-85; The Journal of AID Atlanta, 1985-86) and the Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance (ALFA Newsletter, 1973-76; Atalanta, 1977-94). Magazines covering Atlanta’s gay entertainment highlights also proliferated. The southern gay travel magazine Cruise was founded in 1976, followed by subsidiary publications Cruise Weekly covering gay entertainment events in Atlanta, the short-lived newspaper Cruise News, and Score, a pornographic magazine aimed at gay men. The latter publication drew the attention of the Fulton County solicitor, who issued arrest warrants for owners and employees of Score in 1979 for “distributing obscene materials.” Cruise, however, remained in print till 1984, and other publications invested in local LGBTQ+ nightlife, politics, and news followed in the 1980s: Gaybriel (1979-80); The Gayzette (1980), later called The Gazette (1981) or Metropolitan Gazette (1982); Sunset People (1980-83); Pulse Magazine (1984). As these LGBTQ+ travel guides, bar magazines, and newspapers of the 1970s and 1980s announced, Atlanta was a “gay mecca,” full of stories to tell. LGBTQ+ journalists remained at the forefront of the push for queer news coverage, and Georgian journalists have achieved critical “firsts” in the field. Sometime before 1980, James R. Moody became the first openly gay columnist for a mainstream Atlanta newspaper, and nearly forty years later Augusta native Raquel Willis became the first transgender woman to serve as executive editor of the most widely circulated LGBTQ+ monthly publication in the United States, Out magazine.