Censorship

-

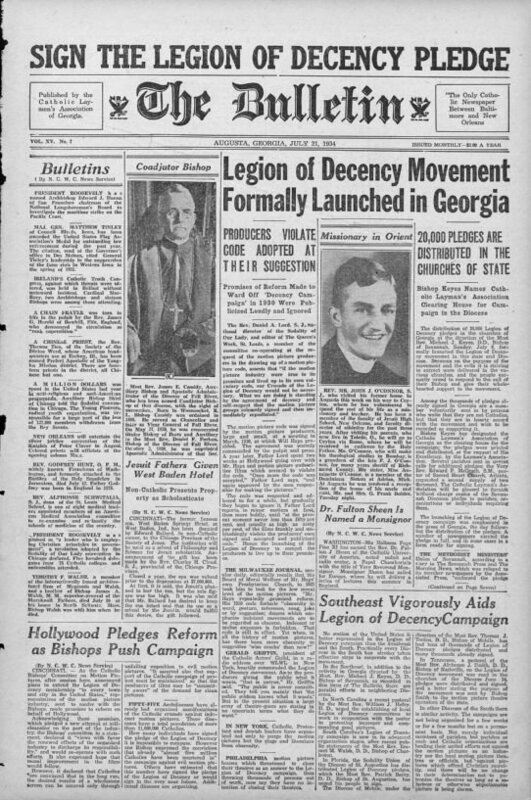

Frontpage of The Bulletin, a publication of the Catholic Layman's Association of Georgia, announcing the launch of the Legion of Decency Movement in Georgia.

Courtesy of Roman Catholic Diocese of Savannah via Georgia Historic Newspapers.

-

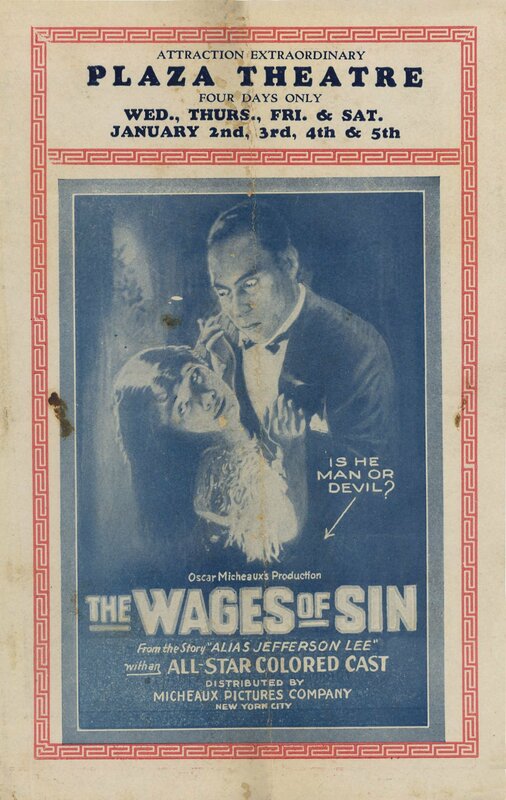

Circular advertising The Wages of Sin at the Plaza Theatre in January 1929, featuring an "all-star colored cast." The cover features a man holding a frightened woman. Next to the image, a question is posed: "Is he man or devil?" While many race films provided a more nuanced portrayal of Black Americans than other films of the era, censorship laws prevented equitable representation in film and reinforced racial stereotypes.

Courtesy of Middle Georgia Archives, Charles Henry Douglass, Jr. Business Records, 1906-1967.

-

The African American entrance at the Roxy Theatre in Atlanta, 1954. The Roxy was one of few theaters open to Black audience members. But seating, like the entrance, remained segregated.

Courtesy of Georgia State University. Libraries, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, 1920-1977.

While theatrical productions throughout Europe and America had been subject to calls for censorship before the rise of motion pictures, the increased popularity of films brought new attention. Calls for standardized censorship came at the very beginning of film’s introduction in America, with many concerned about film's potential to corrupt the American public. In 1907 this led to the institution of the first government-administered “pre-exhibition” censorship system in Chicago. While some producers and film executives sued their state censorship boards for free speech violations, early Supreme Court rulings established that films were not fully protected under the First Amendment and deemed them an “insidious” threat to the moral good and welfare of the nation. In 1934 Hollywood studios created the Motion Picture Production Code, also referred to as the Hays Code. The Code set industry guidelines until 1952 when the Supreme Court afforded motion pictures First Amendment protection. After the court's ruling, statewide censorship also decreased, with the Production Code only upheld by local boards and reviewers, which performed with varying degrees of intensity. Roughly one hundred such boards once existed nationally, including in Augusta, Valdosta, and Atlanta, which had a particularly active board. However, by 1965, few remained active.